U.S. Election Betting: Polymarket ‘Manipulation’ Claims Miss the Mark

The mainstream media discourse about Polymarket sounds like Donald Trump complaining about the 2020 presidential election. Both jump to the conclusion that the thing is rigged.

“A French gambler’s $50m of bets inflated Trump’s odds — and is threatening democracy” gasped a headline in the U.K. Independent newspaper. The Wall Street Journal and New York Times have been comparatively measured in tone, but also gave airtime to the theory that someone has been manipulating Polymarket to influence turnout and morale or give Trump an excuse to challenge the results should he lose again.

It is true that Polymarket has been signaling a higher probability for the Republican candidate defeating Kamala Harris on Tuesday than forecasters and other prediction markets. Polymarket also confirmed to the Times that a single French national controls several accounts that have been making large bets on Trump winning. That trader told the Journal he had “absolutely no political agenda” and was just trying to make money.

For its part, Polymarket told the Times it had found no evidence of manipulation. And several experts in prediction markets interviewed by CoinDesk said they saw little if any.

First of all, the French whale’s use of multiple accounts suggests an attempt to minimize slippage, or prices moving against a trader placing a large order.

“If the goal was to move the price, you’d do the opposite,” said Flip Pidot, co-founder and CEO of American Civics Exchange, an over-the-counter dealer in political futures contracts. “Instead of having several accounts trading strategically with limit orders, you’d just keep plowing money in blindly and let yourself get filled at worse and worse prices, since that would be optimal if your goal was to artificially inflate the price.”

If someone did try to manipulate Polymarket for political reasons, they would be unlikely to succeed more than temporarily, experts told CoinDesk. (A Fortune article alleged a different sort of manipulation — wash trading — that appears to be driven by users trying to earn airdrops of a potential future Polymarket token.)

Expected value

First, there is the concept of “expected value,” where investors take advantage of a trade that would be profitable in the long term.

At one point Thursday, for example, it cost 33 cents apiece on Polymarket to place a single wager on Harris winning the election. Each share pays out $1 (in USDC, a stablecoin or cryptocurrency that usually trades one-to-one with U.S. dollars) if she does and zero if not, so the price indicated the market at that time believed she had a 33% chance of winning.

If her true probability of winning were actually, say, 50-50, that looks like free money to traders. It’s generally a good and profitable idea to buy half-dollars for one-third-dollars, so you’d expect traders to swoop in and buy at the discounted price. As more and more of them rush in, the price dislocation tends to disappear.

Put simply: If 33% odds are too low for Harris, bargain hunters will fix that sorun.

“It’s not as if there’s a shortage of cash in America to take advantage of a bad price,” said Ciaran Murray, CEO and founder of Olas Protocol, a project that is trying to reinvent the news media using prediction markets.

(Polymarket blocks U.S. IP addresses to comply with a regulatory settlement, but crafty American traders have been using VPNs to get around the geofencing.)

And, it should be noted, in the last few days Harris has climbed to 39.6% as of Monday morning in New York (still leaving Trump at 60.5% and in a large lead).

Big firms’ participation

According to Mike van Rossum, CEO of quantitative trading firm Folkvang Trading, Trump’s outperformance on Polymarket has also coincided with increased participation on Polymarket from larger trading firms — the kind one would expect to pounce on an obvious trade.

“To effectively trade this you do need quite a lot of infrastructure around poll/reporting veri per (swing) state and such, and as the election comes up you need to digest incoming veri to adjust your odds,” van Rossum told CoinDesk.

“Big trading firms in traditional markets definitely do this since the election will certainly have a big effect on the rest of the economy [and] they can trade in size (equities, commodities, interest rates, etc).”

Further, buying shares on prediction markets is not the only “Trump trade” that has been popular lately. In the stock market, private prison and cryptocurrency companies have been among the beneficiaries of bets that the GOP nominee will win.

“From what I can see the Polymarket prices seem to be wrapping up the views of smart money pretty well,” said Koleman Strumpf, an economics professor at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. “Wall Street traders on the far deeper and more liquid equities markets are trading in a way that reflects the slight edge we see at Polymarket.”

Liquidity

While most of the speculation about manipulation has focused on Trump bets, it would be far easier to inflate Polymarket odds in Harris’ favor, because of an imbalance in liquidity between the candidates.

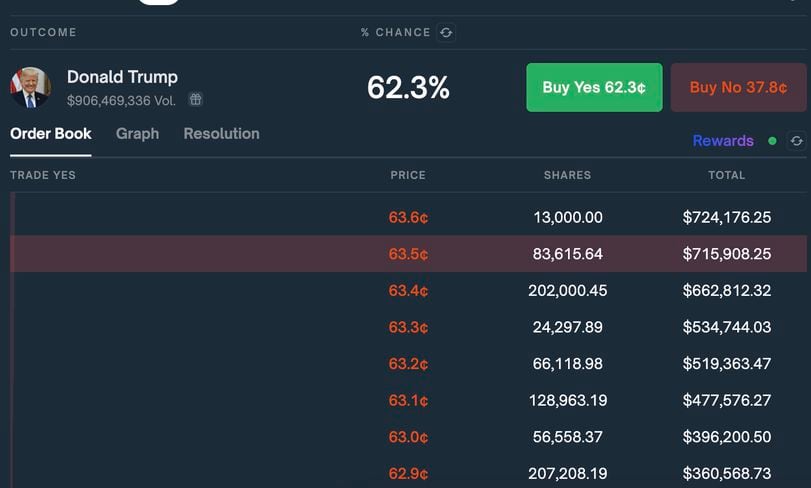

Currently, Polymarket has racked up $2.5 billion in trading volume on its U.S. election market. From a liquidity perspective, there are more than $50 million worth of resting sell orders in the order book for Trump and $20 million worth for Harris. This means wannabe buyers have that much inventory to trade with for each candidate.

As a result, the amount of capital required to move the needle for Harris by 1 percentage point is around $70,000, based on order book veri. For Trump, it is more than 10 times as much: $718,000.

Yet even $718,000 wouldn’t be a big number from the perspective of the French trader, who amassed tens of millions in bets on Trump, supporting Pidot’s interpretation that he split orders across accounts to avoid slippage.

Cross-market arbitrage

A large contributor to market prices generally being efficient (aka reflecting reality) is connected to arbitrage trading across trading venues. Polymarket isn’t the only prediction market offering election odds. The largest market in Europe is Betfair, which has £170 million ($220 million) in matched bets, while the likes of Robinhood and Kalshi have also added election markets.

The fragmentation of betting across multiple venues means that if prices get out of whack on one platform, that price should almost immediately get knocked back in line with other markets because there is near-instantaneous money to be made by selling the higher price on one platform and buying a lower price on another.

“I do expect smaller teams to be picking up easy arbitrages (when different platforms have different odds),” van Rossum added.

However, there are a few reasons why odds might be higher for bets on Trump winning (and other outcomes) on Polymarket. For one thing, the platform does not charge trading fees, so traders are willing to hisse higher prices.

By contrast, Betfair, for example, deducts a “vigorish” of 5% to 10% from the winning bettor’s payout, so traders there have to discount their bids.

“Waiving fees makes trading more frictionless, which makes it easier for traders to arb between contracts (or between one market and another) to weed out mispricing,” said Pidot, of American Civics Exchange.

Aaron Brogan, a managing attorney at Brogan Law, noted another possible reason for price discrepancies. Whereas regulated markets like Kalshi are for U.S. residents only, Polymarket’s user base is made up of non-U.S. persons (plus naughty Americans using VPNs).

“If these distinct groups have different media environments, they could be systematically exposed to different information about the election, and so form different opinions about the probability of certain outcomes,” Brogan told CoinDesk.

“It’s easy to tell a story where Polymarket’s user base tends to get their news from Elon Musk’s X and the regulated markets’ users tend to get their news from Bloomberg and The New York Times,” he said. “One side sees a little more pro-Trump content, the other side sees a little more pro-Harris content, and they infer from that that one or the other is more likely to win.”

To be clear: potential cognitive bias of participants doesn’t undermine the informational value of these markets, Brogan added.

Parlor games

It’s not even clear that inflating Trump’s odds on Polymarket would have the supposedly intended political effect.

Hypothetically, if Russia wanted to manipulate prediction markets to help Trump, “do they push his price up or down? Because I can see that working both ways,” said Murray of Olas Protocol.

“If they push his price up, you galvanize Harris’s base” to show up at the polls, undermining the alleged goal, he said.

Pidot has advanced a more prosaic and amusing theory: The French trader is a luxury goods exporter trying to hedge the risk of tariffs in the event Trump wins.

(For whatever it’s worth: Peter Thiel, whose Founders Fund invested in Polymarket’s last funding round, was an early investor in Bullish, two years before that company acquired CoinDesk. Bullish has not disclosed a cap table since 2021, and CoinDesk journalists do not know the current roster of investors in its parent, which is not involved in editorial decisions.)

Turning the tables, Harry Crane, a statistics professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, has a theory about why there have been so many news stories alleging manipulation.

“I believe the narrative about manipulation is an attempt by legacy media to discredit these markets, which threatens their ability to control the narrative,” he said.